Club des Amitiés boxing club, Goma, Nord-Kivu November 2011

I am an orphan and am alone in the world. I work with the mechanics here in the Kibabie market in Goma, which is what feeds me, but it is difficult. Before that I was a street boy. The Club des Amitiés is my home.

I am an orphan and am alone in the world. I work with the mechanics here in the Kibabie market in Goma, which is what feeds me, but it is difficult. Before that I was a street boy. The Club des Amitiés is my home.

I was forcibly recruited to the Mai Mai milita in 2006, when I was 12, and I left them in 2009, fleeing. My Father is dead and my Mother lives outside of Goma in the countryside. During my military life I went through much suffering. I now live in a friend’s home and carry things for people as a job, so as to get money for food. In order to eat I must work very hard.

I was orphaned, losing my father age one. My Mother who had been my support has been weakened by sickness. The Club des Amitiés has become my family. I was not in the army or militas, but after the rebel commander Laurent Nkunda took the city of Bukavu I witnessed my sisters being raped by soldiers. One became infected with AIDS and later took poison to kill herself.

After my Mother died things became hard, particularly as their were 12 of us. I was later abducted into Thomas Lubanga’s army, in Bunia, Ituri province. I fought there for four years. I finally left them with the help of Human Rights Watch. Since then I have been working as a mechanic’s assistant here in Kibabie, and boxing at the Club des Amitiés. I am the Bantam weight champion for eastern Congo.

These remarkable stories, drawn from registration interviews, provide a snap shot of the back ground of the members of a boxing club for street boys in Eastern Congo which is now run by the NGO, the Centre d’Assistance et de Réinsertion du Kivu. Most are orphans or demobilised soldiers or both, with all of the latter recruited as child soliders when between the ages 10-14. Some display signs of trauma, appearing silent and withdrawn, others are energetic and alert. Several are street boys and border line streetboys although there is some lack of precision to the term as nearly all streetboys in Goma do sleep somewhere. Many of them work in the informal mechanics market of the Kibabie slum in Goma, generally as assistants to the older mechanics. All, including those living with parents, relatives or friends, have precarious existences and say they must work to find enough to eat, meaning that the households where they live do not have the means to care for them. Several say that they are “alone in the world” and that the boxing club, the Club des Amitiés—the friendship club—is their home.

These remarkable stories, drawn from registration interviews, provide a snap shot of the back ground of the members of a boxing club for street boys in Eastern Congo which is now run by the NGO, the Centre d’Assistance et de Réinsertion du Kivu. Most are orphans or demobilised soldiers or both, with all of the latter recruited as child soliders when between the ages 10-14. Some display signs of trauma, appearing silent and withdrawn, others are energetic and alert. Several are street boys and border line streetboys although there is some lack of precision to the term as nearly all streetboys in Goma do sleep somewhere. Many of them work in the informal mechanics market of the Kibabie slum in Goma, generally as assistants to the older mechanics. All, including those living with parents, relatives or friends, have precarious existences and say they must work to find enough to eat, meaning that the households where they live do not have the means to care for them. Several say that they are “alone in the world” and that the boxing club, the Club des Amitiés—the friendship club—is their home.

For an indication of what the typical experiences were for young soldiers in the armed groups in eastern Congo it is worth considering the situation of the last of the boys mentioned here, Kedrick, and who was in the forces of Thomas Lubanga, and the Union des Patriotes Congolais. This was the most notorious of the armed factions that emerged in the chaos of eastern Congo during the high point of the war years, notable even by the rogues gallery standard of Congolese war lords, responsible for the worst abuses, the most agregious behaviour, human rights violations on a massive scale, including, according to New York based Human Rights Watch: ethnic massacres, murder, torture, rape and mutilation, as well as the recruitment of child soldiers. At one time it had over 3,000 child soliders between 8 and 15 under its command, the largest number in Africa. The demobilisation programme by Human Rights Watch Kedrick refers to involved this New York based agency directly contacting all the armed groups in Congo and advising them that they were in contravention of international law in employing child solders and should discharge them. Remarkably, most complied although the use of child soldiers in Congo is hardly over even now. Thomas Lubanga is currently at the International Criminal Court in the Hague facing a war crimes trial.

For an indication of what the typical experiences were for young soldiers in the armed groups in eastern Congo it is worth considering the situation of the last of the boys mentioned here, Kedrick, and who was in the forces of Thomas Lubanga, and the Union des Patriotes Congolais. This was the most notorious of the armed factions that emerged in the chaos of eastern Congo during the high point of the war years, notable even by the rogues gallery standard of Congolese war lords, responsible for the worst abuses, the most agregious behaviour, human rights violations on a massive scale, including, according to New York based Human Rights Watch: ethnic massacres, murder, torture, rape and mutilation, as well as the recruitment of child soldiers. At one time it had over 3,000 child soliders between 8 and 15 under its command, the largest number in Africa. The demobilisation programme by Human Rights Watch Kedrick refers to involved this New York based agency directly contacting all the armed groups in Congo and advising them that they were in contravention of international law in employing child solders and should discharge them. Remarkably, most complied although the use of child soldiers in Congo is hardly over even now. Thomas Lubanga is currently at the International Criminal Court in the Hague facing a war crimes trial.

I trained and boxed together with these boys for four months earlier this year after stumbling across their club when looking for a trainer and finding their coach, Kibomango, who is Congo’s super welter champion. I did not know their stories, what exactly they did, or where they came from. But they accepted me among their number and we trained hard together at 630 every morning here in this slum, spared and boxed with each other.

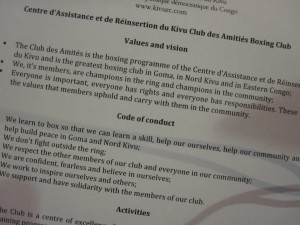

Now things are different. I am no longer their fellow student and they and their club are part of a structured youth programme, adopted by a local NGO. The club now has good equipment and the boys receive individual mentoring, access to an education programme and support and mediation where needed. It isn’t much, but it’s a start. Among other things, the club has a values and mission statement and a code of conduct. It’s plastered on the wall of our gym and there for all of Goma to see. It has one element that is important for young men who are among the most marginalised members of this community : Everyone is important, everyone has rights and everyone has responsibilities.

Now things are different. I am no longer their fellow student and they and their club are part of a structured youth programme, adopted by a local NGO. The club now has good equipment and the boys receive individual mentoring, access to an education programme and support and mediation where needed. It isn’t much, but it’s a start. Among other things, the club has a values and mission statement and a code of conduct. It’s plastered on the wall of our gym and there for all of Goma to see. It has one element that is important for young men who are among the most marginalised members of this community : Everyone is important, everyone has rights and everyone has responsibilities.

Thank you for writing this impressive story, so painful to imaginethose horrors, and then so enlightening to imagine the power of survival and hope! and to know you continue to amaze and inspire. and so much to do, now the story reminds me of… The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/