It is difficult to describe the feeling you experience when crossing the Congo river from the city of Brazzaville to Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of Congo’s ragged megalopolis and capital city. There is a sense of expectation and excitement and, one must admit, trepidation. It is like knowing you are entering an experience where you don’t know what is going to happen and what you will see or do. The river is so massive and deep and fast flowing here even though it is miles wide, as though it is draining a continent, which it is, and the water is a muddy red and full of clumps of green water hyacinth the size of coffins and small cars that are coming downstream. And then you reach the opposite shore and see all the river boats and barges tied up at the port, having come from far upriver. There are huge log booms rafted together with little straw huts on top of them and people living there with their cooking fires and one wonders of their journey downriver to the city. I imagine the boats and the river bank as largely unchanged since Joseph Conrad’s time, when he was a river boat captain here in 1889 and wrote Heart of Darkness.

The port itself is a chaos of snarling officials and frigthened people that could be conjured up by Hieronymus Bosch. You step off the boat and up a gang plank and then cross a fenced corridor for traffic to the bigger ferries, crowded with people and luggage, plus the stevedores staggering under enormous bundles—cotton and rubber wrapped in canvas. When we arrive at this cattle chute there is pushing, shouting and fights going on, and then the port police wade in hitting people with truncheons, clearing a path for us, relative VIPs from the fast ferry, to cross.

Nothing is easy in this country for which the term “negative excellence” was coined. People are tough, arrogant even, and fairly mercenary about what they expect to get out of you, most interactions with officials or police a pretext for graft. There is more hustle than elsewhere in Africa, more aggression, more of everything. Honesty and civility are luxuries this brutalised society does not have. It is also dangerous, if not exremely so, but walking the streets is not advised, according to friends experienced here, and places far worse, one risk being rogue policemen who rob foreigners—at gunpoint.

When we arrive at the customs post Jean-Jacques, a security consultant I met in my hotel the night before in Brazzaville and was on my ferry, is there looking relaxed and well dressed. He asks for my passport, hands it to his fixer to whisk through the dreadful immigration service that is a front for shake downs, asks what hotel I am at, says he knows a better one, snaps open his phone, speaks to someone, tells me his driver will take me there and then says that we will have dinner together that night.

I have two days in Kinshasa to get UN accreditation and get on a UN flight to Goma, the capital of troubled Nord Kivu province, where most of the UN peace keeping troops are still based, and is the centre of a humanitarian disaster that has continued without end for 15 years. More than a dozen armed groups are active in the Kivus and, on past experience, it is a place where awful, even unspeakable, things happen.

***

In V.S. Naipual’s novel A Bend in the River Congo is described as a country alternately making and breaking. After five years of civil and regional wars that may have killed 5m people from 1999-2004, it stopped the breaking and was making again when it crafted a peace agreement, invited in UN peace keepers, pulled out of war and set the basis for recovery. An imperfect government emerged from imperfect elections and basic personal and political freedoms were re-established, a free press and human rights organisations and civil society enabled. The IMF was invited in, the government stopped printing money to pay for everything and international aid and investment returned. The economy stabilised, and then took off, poverty began falling and a country that had become the world’s worst humanitarian disaster pulled back from the brink.

Five years later the shine has come off the good news story and the country is on a downward trajectory—the breaking phase again. It is hard to pinpoint the exact source of the sense of malaise one finds in Kinshasa and elsewhere but there is a definite sense that things are no longer going in the right direction and that a country long a byword for suffering, and renowned for legendary corruption and malgovernance, has returned to familiar ways. Peace has not come to the troubled east of the country, where intractrable conflicts involving a dozen armed groups grind on, defying solution, and throwing up new complication, suffering and dysfunction. At the national level a strong and stable government did not emerge from the peace process and elections supervised by UN peace keepers, rather a multiple number of parties that are not singly dominant. One of the largest—led by Jean-Pierre Bemba, a psychotic former warlord who had participated in the peace process, rejected the result and started a week long battle in the streets of Kinshasa that killed 3000 people. Bemba sought refuge in the French embassy and was allowed to leave Kinshasa but was arrested in Europe last year and is now on trial for war crimes at the International Criminal Court.

The president, Joseph Kabila—who assumed power at age 29 when his father was assassinated in 2001—has been catapulted from well deserved obscurity to the presidential office—almost the only institution regarded as capable of holding the country together. On a previous trip here one well placed western intelligence source described him as a 29 year old president who smoked dope and watches TV all day and is unprepared for office. He has defied critics since then and has had some successes, including overseeing the peace process, elections and stabilising the economy, but is not a charismatic figure and is essentially leader by default, beholden to a shadowy group of advisors and power brokers who are a real source of power. He is not popular in parts of the country and faces re-election next year. It is knowledge of this weak political position that is probably driving much of the down draft—the human rights situation is deteriorating and harassment of press, civil society organisations and political parties are on the rise; a more authoritarian style of government is ascendant, one that can leverage its own weak position and secure survival by whatever means necessary.

The economy, previously one of the feel good stories, is also on the slide: while commodity prices were booming the government decided to tear up its mining contracts under which foreign companies—many of them Canadian—had agreed to invest in one of the riskiest jurisdictions in the world. Overnight billions of dollars of value evaporated and since then the global economic collapse has hit the sector hard—most mining investment is on hold and many of the existing mines shut down—200,000 jobs have been lost. It is another lost opportunity—the investment could have been locked in and be carrying the country through the downturn. Instead the government is now struggling to even pay civil service and army salaries on time. Macro-economic stability, the bedrock of wealth creation and poverty reduction, is now in abeyance, and the reform programme with the IMF has collapsed. Financial irregularities—read corruption—fiscal and other indiscipline has led to the suspension of the IMF’s assistance, the pre requsuisite for recovery in any African country.

***

Jean-Jacques, my security consultant friend, is a mixed race Congolese who heads up the local office of a company established by ex-British Army officers that has contract work in Iraq, Afghanistan, South Africa, Nigeria and both Congos. They handle everything from company security guards to hostage negotiations, risk assessment and political advice. We meet for dinner at the Kinshasa Golf Club, a gorgeous spot with tennis courts, a bar and a good restaurant—reputedly the most expensive in the city—that fronts on to the lush green golf course tended by an army of local grounds keepers and, in this tropical climate, need never be watered.

When I arrive there are diplomats and local businessman arriving for an after work tennis game and a drink. The local European business community, most of them Belgian, are a group with equal measures of sophistication and toughness. The latter they need loads of and whatever their privileges and wealth, they have lived horrendous experiences as well, going through war and regime change as well as the day to day of living and doing business in one of the riskiest and most corrupt places on earth. Many have made and lost fortunes, even been ruined, including during the last violent change of power in the early 1990s when most large merchants had their stores and wharehouses looted. It is not an experience any will forget, and to this day there are scarely any wholesalers in the capital or elsewhere in the country either. All supply chains are short with no more than a few days stock. It is not an efficient way to do business—hence the expensive prices—but it is another example of the risk aversion strategies and short term decisions that dominate how business is done here. No one invests for the long term, in production or things that require a long term pay back. You have to have already earned your money and be prepared to lose it all.

***

Waiting for Jean-Jacques I am seated across from an older American with long grey hair in a pony tail sipping a tall glass and talking into his cell phone. I imagine him as a mining tycoon or an old Africa hand. Are Americans fundamentally different people? There is something forthright and open—but positively so—in their bearing wherever in the world one finds them. However, badly that may play elsewhere and at other times I have to welcome the can-do positivism here as an antidote to European negativity and the local fatalism. The tycoon seems to be having a heart to heart with an estranged off-spring:

“I’m not ashamed of what I’ve done…”

Of what! That he ran off with his secretary and contracted out Junior’s parenting to a New England boarding school?

“…but nothing I can say….. is going to….. make a difference….. with something that…. will decide… what you are gong to do with your life.”

Jean-Jacques arrives and, from the politicians and businessmen he greets on the way to our table, it is apparent that he is well connected. A youthful looking early 50s, he was brought up here, has lived through war, regime change and the other chaos of the last decades and has seen it all. He has also lived and worked in New York and elsewhere and tells me about going to the Montreal premier of Scarface in 1983 and being arrested for breaking into his own car. I am about to make a crack about racist Montreal cops but hold back as I suspect that this man, comfortable in many worlds, has no time for North American style racial victim hood.

He agrees that the country is entering the “breaking” phase and that the fumbled mining review is an example of the record of greed and mismanagement overtaking prudent policy. This has also led to the collapse of most of his business as his mining clients have suspended operations or left altogether. He is a realist who seems resigned to being disappointed by this country in future. His disdain for the government is clear and he says that country risk is still extremely high and that most business is conducted on a short term quick pay back basis; no one invests for the long term, and generally pursue commerce—trading easily saleable items with short transaction terms—over production. This is a reaction to the adverse business environment and is why prices for everything are so high—there is a risk premium built into the cost of all goods and services and he doesn’t see that changing in the future.

We are joined at our table by a diplomat from a—best un-named—western embassy. Now in Congo for his fourth tour of duty since the 1970s his insights into the local business community are as shocking and revelatory as any other conversation here on whatever topic from politics to business. After the second Tembo—a local beer from Katanga with a retro graphic of an elephant on the label—my friends suggest moving on elsewhere, their recommendation for which is intriguing enough:

“It is not the best restaurant or bar in Kinshasa but it is perhaps the most interesting. It is the place where the gangster takes his girlfriend, it also the place where the policeman or the politician takes his girlfriend. And there are lots of Europeans there too. You will see. The wine list is competent”.

***

Arrival at the UN section of the airport at 5:00 AM after a taxi ride through the slums of Kinshasa is a morning come too early. The UN peace keeping operation, MONUSCO, is a state within a state. It operates its own airports and scheduled passenger services throughout the country, has its own police force, operates a multi-national army of 17,000 soldiers and 3,000 civilian employees as well as contractors, sub-contractors and local hires. It has whole operational divisions for peace enforcement, demobilising combatants, political affairs, civil affairs, elections, human rights, child soldiers, sexual violence against women—a plague in this country on a scale unknown anywhere else in the world—and runs its own radio station, Okapi. It is what put this failed state embroiled in civil war with a dozen rebel groups and half as many foreign armies, back together again. It is over 10 years on and that process is neither complete nor perfect and the unfinished business is what keeps it here, costing US$1.5bn per year—the largest and most expensive peace keeping operation in history. No one wants it to stay and everyone knows it cannot leave.

Arrival at the UN section of the airport at 5:00 AM after a taxi ride through the slums of Kinshasa is a morning come too early. The UN peace keeping operation, MONUSCO, is a state within a state. It operates its own airports and scheduled passenger services throughout the country, has its own police force, operates a multi-national army of 17,000 soldiers and 3,000 civilian employees as well as contractors, sub-contractors and local hires. It has whole operational divisions for peace enforcement, demobilising combatants, political affairs, civil affairs, elections, human rights, child soldiers, sexual violence against women—a plague in this country on a scale unknown anywhere else in the world—and runs its own radio station, Okapi. It is what put this failed state embroiled in civil war with a dozen rebel groups and half as many foreign armies, back together again. It is over 10 years on and that process is neither complete nor perfect and the unfinished business is what keeps it here, costing US$1.5bn per year—the largest and most expensive peace keeping operation in history. No one wants it to stay and everyone knows it cannot leave.

A UN airport is like a military operation with army staff operating the check-in and verifying the flight manifest. It is also like a university fraternity outing and many of the passengers in the departure lounge are UN civilian staff, 20 and 30 something Europeans and North Americans heading back to their postings in the far flung provinces. I chat with Stephanie, a Belgian working in the elections office. She’s been here a year and a half and seems bewildered and burned out. For one, Kinshasa frightens her—it is a scary place, and not the easiest choice for your first job abroad. Her division is supposed to be helping the government to update the electoral register and mount a reasonably clean and open election across DRC’s sprawling territory that is the size of western Europe and has no roads. She says that the election process is floundering, the government does not have the capacity or the money—as much as $100m—to do it and the UN does not have the mandate or the money to take over and do it for them either. But she is mostly horrified that the government is not interested in trying either and she does not see any progress in what she is doing or where the country is going.

Walking across the tarmac in the UN section of the airport past Soviet military aircraft painted in UN white we board for Goma, in troubled Nord Kivu province, nearly 2,000 km to the east. My seat mate is a baby-faced Russian air force major who is an amalgam of the new Russian, comfortable with the modern world, and the old Russian, nationalist, parochial and paranoid—he listens to Russian hip hop on his MP3, studied at Collège militaire royal Saint-Jean Quebec, loves the NHL, day trades foreign currency, thinks the Dow Jones will fall by half to 4000 points after what he believes is the imminent and complete economic collapse of the US—the Russian military’s own equity analysts have told him so—and is certain that 9/11 was an American plot.

***

Clearing the green hills of the Massisi plateau in Nord Kivu our plane skims over Lake Kivu and arrives at the UN airport in Goma beneath the perfect cone of the still active Nyiragongo Volcano. It last erupted in 2002 and covered half the town in lava. Even now the area is still covered in soot-like volcanic ash which gives the town its grimy appearance. The local “Volcanological Observatory” has just issued a fresh warning that there are early signs of an eruption and this “could be at any time, in two days, or a week or two, but not later than two months”. Once a beautiful lake side town of villas and flame trees Goma is now an overcrowded city of 300,000 people many of whom are internal refugees displaced from the countryside in the fighting and violent upheavals that have engulfed this province continuously for the past 15 years. The complexity of these conflicts and the actors involved, past and present, is overwhelming, even for an experienced analyst. One agency report describes it as “multi-fronted, tremendously unpredictable and complex.” Indeed.

Clearing the green hills of the Massisi plateau in Nord Kivu our plane skims over Lake Kivu and arrives at the UN airport in Goma beneath the perfect cone of the still active Nyiragongo Volcano. It last erupted in 2002 and covered half the town in lava. Even now the area is still covered in soot-like volcanic ash which gives the town its grimy appearance. The local “Volcanological Observatory” has just issued a fresh warning that there are early signs of an eruption and this “could be at any time, in two days, or a week or two, but not later than two months”. Once a beautiful lake side town of villas and flame trees Goma is now an overcrowded city of 300,000 people many of whom are internal refugees displaced from the countryside in the fighting and violent upheavals that have engulfed this province continuously for the past 15 years. The complexity of these conflicts and the actors involved, past and present, is overwhelming, even for an experienced analyst. One agency report describes it as “multi-fronted, tremendously unpredictable and complex.” Indeed.

Much of the area’s problems started with the Rwandan genocide in 1994 that killed 900,000 people nearly succeeding in their goal of wiping out the Tutsi minority. The senior perpetrators of the genocide fled to Goma and it and the surrounding refugee camps for a time hosted over 1m Rwandan refugees. This group has since transformed itself into a Hutu rebel movement, the Forces Démocratique pour la Liberation du Rwanda (FDLR), led by the members of the ex-Rwandan army and government dedicated to reconquering Rwanda. The FDLR, who seem to be human evil personified, are now the hard core of a hard core problem, a vicious rebel group of 6000 with a strong military command and control structure who have enmeshed themselves into Congolese society and prey upon the communities of North and South Kivu and beyond. In and out of alliance with the Congolese state—implicitly or explicitly—several times over the past decade and a half, they are now public enemy number one and, after years of ambiguity the government in Kinshasa has dedicated itself to resolving the FDLR problem once and for all, having just invited in the very tough and professional Rwandan Army to mount joint operations. The joint operations with the Rwandans—over January and February—have not wiped out the FDLR, but it has displaced them from their main bases and forced them further into the countryside where they are now, marauding across both North and South Kivu. The operation has also displaced 800,000 people in the last four months, resulted in hundreds of deaths and been criticised by NGOs and human rights groups as a man made humanitarian disaster. But the FDLR is also a man made disaster and you cannot make an omelette without breaking eggs. With the Rwandan Army now departed, the job of taking out the FDLR is meant to be finished by the shambolic Congolese army, the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) backed up by MONUC troops.

Even this nasty conflict is almost a side show to the other clashes grinding on in the Kivus. There is, for one the great, and recently concluded, “Battle of North Kivu” in which a Congolese former rebel commander Laurent Nkunda who had integrated into the national army under the peace process, opted out of it again last August, taking all his soldiers with him and forming the Congrès national pour la défense du peuple (CNDP), essentially the remnant of a militia formed a decade earlier to protect Congolese Tutsis—the Banyamulenge—from the genocidal Rwandan Hutu FDLR. Despite military assistance and full backing of MONUC, the government army collapsed in the face of the better motivated CNDP and were kicked out of most of North Kivu, falling back to Goma, where the front lines stabilised. A fresh peace process in October resulted in a fragile accord with the CNDP who have agreed to rejoin the FARDC. That process is very uneven—as I will find out.

Yet another side to the many sided Kivu conflict is the presence of a further dozen or so other armed groups—some of them Ugandan, but mainly the Mai-Mai militias, which were ostensibly formed as self-defence community militias during the great Congolese civil and world war of the early 2000s but which have since taken on the predatory features of war lord groups themselves named with an alphabet soup of acronyms—PARECO, Rocket et al. The Mai-Mai militias, who are local, have more of a stake. They have been nominally allied with the Congolese government for the past decade, but more recently that has fragmented—when the government army was defeated in the Battle of North Kivu and fell back to Goma in October the Mai-Mai’s turned on them and fought pitched battles, accusing the army of cowardice and abandoning them and their communities without a fight. The two sides are nominally back in alliance again but the relationship is fluid and could easily change, just like much else here.

Violence, banditry and killing remains common throughout the communities and countryside of North and South Kivu and no one even knows who is involved: FDLR, the Mai-Mai’s, the CNDP, FARDC, PNC—Police Nationale du Congo—or freelance gun men who have fragmented from all of the above. For armed groups in the Kivus loyalty and identity is something fluid.

***

Walking across the road from the airport to UN headquarters I need to link up with the Public Information Office and set up a programme of interviews and field visits for the 10 days I am here. Trouble comes immediately. The public information officer I meet points to the UN press pass dangling around my neck and says: “if the police see you with that without having got Congolese media accreditation first you will be arrested. You can’t come to the Kivus without local accreditation. Our office in Kinshasa should never have issued you that pass without getting you accredited; it is easy to do it there, it isn’t easy here. They are basically harassing foreign journalists now and the atmosphere for the press is extremely hostile. They have a bad human rights record and they don’t want scrutiny. Some American journalists were arrested for operating without accreditation a few months ago and things have been very tense since then. It might sound petty, but paper work and regulation is what officials use to make life hell for you, that’s the way it is here. You’ll need to speak to William, our director, he will give you a pretty tough talk”.

Walking across the road from the airport to UN headquarters I need to link up with the Public Information Office and set up a programme of interviews and field visits for the 10 days I am here. Trouble comes immediately. The public information officer I meet points to the UN press pass dangling around my neck and says: “if the police see you with that without having got Congolese media accreditation first you will be arrested. You can’t come to the Kivus without local accreditation. Our office in Kinshasa should never have issued you that pass without getting you accredited; it is easy to do it there, it isn’t easy here. They are basically harassing foreign journalists now and the atmosphere for the press is extremely hostile. They have a bad human rights record and they don’t want scrutiny. Some American journalists were arrested for operating without accreditation a few months ago and things have been very tense since then. It might sound petty, but paper work and regulation is what officials use to make life hell for you, that’s the way it is here. You’ll need to speak to William, our director, he will give you a pretty tough talk”.

William is a harassed and theatrical, even camp, Kenyan who has been here too long. “What Kinshasa sent you here without accreditation! What are they trying to do to me?” He puts his head in his hands, and then looks at me through his fingers. “Ok, you will need to sort this out. It isn’t easy but it isn’t impossible. First, go to the immigration office, get them to register you. Then you have to go to ANR—they are intelligence, the local equivalent of the KGB—get approval from them; then you will need to speak to the Ministry of the Interior and get the signature of the provincial minister. It will cost you US$250 as a starter plus whatever else is necessary to smooth things through. It is 2:30 now and today is Friday, you have to get moving. Ahhhhhh!…. I don’t need this today! Ok, look, you are also going to need a fixer to get you through this, you can’t do it on your own, they will give you a very hard time. In fact they will anyway. The ANR guys are not nice people. They hate journalists here, most often they don’t get to touch them but you are arriving here without accreditation and that means you are in their hands. Here, call this number, its Ferdinand, he’s the best fixer in town.”

***

The Great North Kivu Paper Chase

Ferdinand Benge Luwalo is an interesting man in his own right. He’s from near Busango, Walikale, the area that was the scene of atrocities last week that were serious enough to be noticed internationally—77 people were slaughtered by the FDLR in retaliation for having cooperated with the government during the recent joint Rwandan and Congolese army operation against them. He has lived through changes of power in Goma as the city has switched sides, been fought over, or negotiated away and is adept at dealing with difficult situations and difficult people. He has been guiding international journalists for years and has trekked with them through the mountains to meet with guerilla leaders, bailed them out of jail, translated for them and provided every other service. He also runs his own NGO that provides training and education services locally. He speaks English well in a beautiful African way and his manner is both wise and kind. I like him immediately. He sits down asks the situation, agrees terms and we set out with a car and driver through the streets of this grimy town of refugees and fresh lava fields that are already being built and lived on, passing the visible presence of the UN with trucks, jeeps, and armoured personnel carriers or agency vehicles the whole way.

At the immigration bureau we are shunted through a series of offices staffed by languid, mildly hostile people in the beginning of what I suspect is going to be a very slow and unenjoyable process. We end up in the office of a department head, a man in a bad suit with a cigarette dangling form his lower lip whose face is a mask of both officiousness and indifference. After explaining my business I notice on his desk his wedding photos—he is smiling and wearing a tuxedo although perhaps tellingly, in all of them he is standing in front of his wife who is in the background. I mention that his wife looks beautiful and he cracks a smile, but then scowls again and sends us out of the office to a small ante-room with four desks and four people.

How slow, petty and pointless can a bureaucratic process in an African failed state be? Forms are filled out in duplicate, pedantic questions are asked, answers cross-examined and then the first of the four people in the room begins reprocessing information from the forms into their ledger book. The forms are passed to the next desk and the process continues. Most of the questions have a purpose—to search for a blockage that will justify holding up the process or refusing it altogether. At one point I am ordered to return to the airport to get an arrival stamp to prove where I have come from—for a domestic flight—but am able to produce my UN laissez-passez which indicates my flight route and arrival time.

Another man enters the room, points to a chair and barks at Ferdinand to sit down—they are filling out more paper when a second man enters, yells that Ferdinand is blocking a doorway and departs. He returns a moment later with a policeman carrying an AK-47 whom he orders to arrest Ferdinand who is being dragged outside. The first barker intervenes and there is a comic-farcical scene where each of them is pulling him by an arm.

An hour later we are still in the same room and appear to be no closer to the end of the process we have started. Every action, every step is slow and laborious—even deliberately so. At one point my passport emerges from another room and is on the desk of the woman in front of me. She lifts a rubber stamp which hovers over an open page which I assume will now be stamped and we can be on our way. She begins speaking to someone else in the room and puts the rubber stamp down. She picks it up again, and the process repeats itself several times. There is a deliberate message here—your time is not important and we can waste as much of it as we please.

At one point we are ordered away and I suspect that the process is moving to some sort of conclusion. Outside Ferdinand says: “I have no friends here. These people have no friends either, they have lost their humanity. Their job is to make things difficult, to search for a blockage. These delays and problems are all designed to wear you down so you will give them what they want. I have had journalists who come here from Europe or America and spend their entire time waiting to be authorised either by immigration or intelligence and have to leave without accomplishing anything. The people at this office resent me because I work with white people and they assume that I am making lots of money from them and they want some of it too. That man who wanted to arrest me? He used to work in that office but he was moved somewhere else and now he doesn’t get access to foriegners and their fees anymore. But look, the other is going to return in a moment and we are going to have to pay him something—about $30 will do. Otherwise we will stay here the rest of the night”. At this point I am happy to pay. I have also handed over $150 in fees for a visa from the Nord Kivu provincial immigration office that I find later I don’t need.

***

Our next stop is the provincial headquarters of the Agence National de Renseignement (ANR) Congo’s feared national intelligence agency—which is on a shady side street close to the lake. Ferdinand begins to coach me; “these people are hard and suspicious and will look for problems—they are very difficult”. He is as good as his word.

We enter a walled compound in which the main building is a faded and dirty colonial villa with wide verandas—it is obvious that it had once been a beautiful home but it is now a place where I imagine awful things happen. We register at the guard hut and walk across what had been a garden but is now a beaten dirt yard and are led into a dungeon like basement office when I recall a friend recounting how one meeting with ANR began with a gun being levelled at him. The agent in charge is a short neatly dressed man with glasses whose manner is brusque and mildly menacing. Forms are filled out—in duplicate—and the questions begin. They are sharp and become sharper. He begins thumbing my passport and making notes. “Why are you traveling so much?” I have stamps for, DRC, Rwanda, South Africa and Mozambique, which does not seem like much, but he is suspicious anyway, and begins asking what exact dates I have traveled on. He is shaking his head already and making comments in dialect to Ferdinand. He asks for accreditation from an employer and I hand over an assignment letter from my editor in London which he looks at and asks: “you photo-copied this yourself, yes?” I nod. He tosses it aside. “Anyone can do that. I don’t accept it. Where is your press card”. He snorts at my card and I begin what will be a laborious explanation of why Canadians are not required to register with their government in order to practice journalism, although he stubbornly cannot, or will not, see the point. The conversation is becoming more pointed and he is beginning to make asides over top of me directly to Ferdinand: “I have the same intellectual capacity as him! I don’t have to accept these answers.”

“So why do you wish to work in North Kivu?” I begin explaining that I will be reporting on the humanitarian situation but before I can finish he grabs my UN laissez-passez off the desk and points to the reason for travel section of it that says “security situation in North Kivu” and seems grimly satisfied that I am not telling him the truth. I begin explaining that I have to still work out a programme with the UN but he interrupts “Who is the UN! Congo is a sovereign country. The UN has no authority here. It is us who are in charge”.

This is a raw nerve. The UN peace keeping operation is resented for both overshadowing and holding accountable the local authorities—on human rights and press freedom for example—and criticised at other times for not doing enough to stop more serious abuses. In particular it was blamed by the government for not halting the military advance of the CNDP over the last year in the Kivu campaign in which the authority and capability of the weak Congolese state melted away in the face of a determined rebel army, despite six years of international aid, technical assistance and mentoring from the UN and other agencies. More than that the UN is resented because they are foreign, they are here, and they have all the money, toys and other capability that thinly equipped and badly paid Congolese state institutions don’t have. They are also blamed—perhaps unfairly—for the country’s uneven progress toward peace and stability nationally and—in the Kivus—the spectacular reversals of the last year in which years of peace building collapsed as the province slipped back into civil conflict. This has caused enormous political damage to the authority of both the government and MONUC. But as with an “anti-ism”, scratch the surface and one may find a good deal of self-doubt and self loathing—with all the help and good will in the world the DRC has not succeeded in putting itself back together again.

This intelligence agent is a highly unpleasant man, but the hard questions, the deliberate misunderstandings and misinterpretation and the sheer hostility are all standard interrogation technique—designed to intimidate and unsettle, find inconsistency in your story and make you reveal whatever it is they think you are not telling them. This man also has the professional soul of the security agent—he is prepared to believe the very worst suspicions about you, in fact is desperate to do so, otherwise what is the point of his job? It is dark by now and after a long day without food, feeling exhausted and dehydrated, the night before, the clubs and restaurants of Kinshasa are a distant memory. The Kivus are a world into themselves, a war zone, where horrendous things happen and this man in front of me has the power to do much as he pleases.

“I don’t believe you are a journalist and I don’t believe you are who you say you are”. This is one step away from being called a spy. As I am considering this and wondering where things are heading I reaslise that if he really wants to fuck me up—which he clearly does—then all he has to do is look in my file folder sitting on his desk for my UN press pass, the pass I have been told earlier is a sure-fire ticket to jail.

“Your case is complicated. There are too many questions. I cannot authorise you. You are going to have to come back tomorrow morning and we will continue these discussions”. I am determined not to give in to the intimidation and have been trying to maintain a smile and a cooperative attitude throughout this long hour of abuse. As we stand I say that I understand he is doing his job and that I look forward to seeing him and resolving his questions. But he is not buying this either and seems to have a little speech prepared: “So you are saying that you are going to start to cooperate with me? You know cooperation is not something that is given voluntarily, it is required. And if you are going to start cooperating, what have you been doing up until now?”.

“No, I said that I can answer all your concerns and I look forward to….”

But he has heard what he wishes to hear and silences me with a wave of his hand and points us toward the door.

Back in the car Ferdinand looks worried. “This is a serious problem. He is going to be very hard. These ANR guys can do whatever they want. No one can control them.” I suggest we could contact William and the MONUSCO press office but he dismisses this: “William and MONUSCO cannot help. William is afraid of ANR! We’ve had this before, he always says that UN has to stand back and let the government be the government, that it is a sovereignty issue. They hate the UN anyway, they don’t want interference from the outside, not from the UN, not from anyone. We will have to resolve this ourselves. But look, it is late now. Go back to your hotel. We will sort this out tomorrow. I have seen worse than this, I have even had journalists in jail”.

***

Having gone to bed somewhat rattled I wake up feeling pretty mad—exactly the kind of righteous wrath you need to carry you through all the bullshit and abuse in DRC. Breakfast is served by white jacketed waiters, the coffee—local—is the best I’ve had since leaving home, and the view of Lake Kivu is spectacular with the mountains of Rwanda on one side while straight ahead water stretches to the horizon. The air is cool—we are at high elevation, a relief from the swelter of Kinshasa—and even the architecture of the hotel and the rest of the town is oddly Alpine, buildings with gables and steep pitched roofs. I am thinking that it is an idyllic scene when a UN gun boat comes into view and ties up at the hotel wharf—a luxurious power boat of the kind you would expect to see on a Miami Vice episode, except there is a machine gun mounted on the foredeck, uniformed soldiers running it and a large UN flag fluttering from the stern. Overhead UN military aircraft are flying in low toward the airport a mile away.

Ferdinand arrives and appears relaxed. “I met with the agent and his director and had a very long talk. They are suspicious of you but I know them and I gave them my word that you are who you say you are; they will do it, authorise you. But it will cost you $100”. I ask him if the whole thing had been a money issue, but he explains that ANR is always tough and suspicious and approval from them is never easy. “No one wants to take chances here. They have to be convinced, if they have doubts they won’t do it even if you pay them. Paying can only help get them to do something they are prepared to do already. It is only one day but I know you and that you are who you say you are. They kept asking me if I was sure, and said if there was any problem they would arrest me as well. They are scared themselves—when some American journalists were arrested here a few months ago for operaring without authorisation the immigration staff that cleared them were arrested and are still in jail now. They also just don’t like having journalists here and assume that everyone is a spy. Anyway, this is a troubled province, you will see when you leave Goma”.

We have one more stop to make: the ministry of the interior which will issue the press pass. It is another dingy office with officious officials, languid pace, forms in duplicate and a $250 fee to be paid out. Sitting in a chair in front of the director, there are more pedantic questions and paper work but now, near the end of the process, looking around the office of the director of the ministry of the interior’s press office, a room without windows and a single battered filing cabinet, I imagine how wretched and miserable this man’s life must be—and that the appearance of a journalist parachuting in from another world of affluence, safety and power cannot but stir a mix of emotions: Yankee go home. And take me with you. He extends the press pass and I take it then shake his hand and thank him for his assistance. I am now authorised to operate as a journalist in North Kivu for one week.

At the UN press office I meet William coming out the door: “I’m going on leave to Nairobi, I’m not even supposed to be here! Deal with Mr. Kasonga, I can’t take this place anymore!”

I glance inside his office for a moment and turn around and walk out again. I am in a three sided courtyard of porta-cabins—on one side are housed the military operations of MONUSCO, the Indian dominated peace enforcement detachment, although there are the armies of a dozen other nationalities here too. On the other are the neatly labeled offices of the various UN civilian divisions, human rights, child soldiers, political affairs. I have everything I need.

***

Major Shadool Sharma is the Indian Army’s chief media relations officer for the Kivus and provides my security briefing, and authorises me to do an embed with UN troops, sending me to Rushuro district 200km north of Goma that until recently was a disputed area, although the situation has now been “stabilised”. The FDLR are still operating there but they no longer control the situation; “I couldn’t say that a month ago”. He politely declines my request to go somewhere more exciting. The more contested areas are further north of Rushuro and to the far west side of the province in Walikale district where more serious combat operations are still going on. He explains that their strategy toward the FDLR, who number 4,500 in North Kivu, is purely military—they are not involved in the “soft strategies” to hive off the group’s supporters and help repatriate them to Rwanda—as other UN agencies are involved in—and says they are in active combat operations intended to defeat them militarily. “Unless they come forward with their hands in the air they are to be shot; we are the hunters, they are the hunted”. On the question of whether the FDLR can be defeated, he says that is not easy with any insurgency but that they are slowly closing down the space for them to operate, including access to economic resources—control of mining and timber—as well as food and other resources from the communities they normally prey on.

Others are less sanguine, about the success and wisdom of the current military operations—the government army has not proved up to the task on most things in the past—and are concerned about the humanitarian consequences. An estimated 800,000 people have been displaced and several hundred killed since the FARDC and the Rwanda Army began operations against the FDLR in January. The FDLR, which was previously in a somewhat stable relationship with most communities, and even some of the Mai-Mai self-defense militias, is now in a far more disrupted state and that this is driving an upsurge in violence in the province against communities they view as either cooperating with the army against them or are resorting to greater search and destroy pillage operations from their new bases which are deeper in the forest.

***

My next meeting is with the provincial director of the UN’s DDRRR operations—a programme that targets the soldiers of rebel armies from foreign countries operating in Congo, which is mostly, but not exclusively, the genocidal Rwandan FDLR. His office, he tells me, is inside the former palace of the ex-dictator Mobutu. I jump on a moto-taxi—which is what it sounds like, a seat on the back of a motorcycle—and head off. The taxi drivers are invariably young men who drive like demons through the city weaving in between traffic, running down pedestrians, passing on the centre line between oncoming traffic, slowing down only for the biggest potholes or the huge mud pool lakes that fill the streets after it rains, as today. It seems that I am the only white guy in town taking this form of transport and when people see me or the other moto-taxis pull abreast, they either stare or shout “muzungu”—a simple and obvious declaration: “white man!” But I smile, give them the thumbs up, reach across and slap hands or make some crack. It is my daily dose of humanity when I see people smile back at me, which they invariably do. There are faces in the crowd that seem to hide a thousand shades of emotion and perception, light and dark. I wonder of that outlook and worldview, what do they think when they go about their lives of suffering, blighted ambitions and reduced expectations, in this town where UN staff of every nation in the world are driving up and down in trucks and armoured cars. Although the atmosphere is not directly hostile, there is an undercurrent of suffering and even aggression in this city of the displaced who have been surrounded by 15 years of near continuous warfare. There are few who cannot have been touched directly by conflict, who have not perhaps lost relatives and friends, who have not seen, experienced or perhaps participated in atrocities themselves? The UN is not loved here—stonings have become common enough that many of the UN vehicles now have protective grills over the windows. During the battle for Goma when the CNDP reached the outskirts of town there were anti-UN riots and its headquarters were attacked by rock and Molotov cocktail throwing crowds. One can see joy in people here but there is menace too, in this place of a 1000 shades of suffering and trauma and I see it when I pass through the markets on these crazy motor-cycle rides and catch a 100 pairs of eyes staring at me.

Mr. X, who asks that he not be named, is a large avuncular man with a deep bronchial laugh who rolls his own cigarettes and looks like nothing could surprise him. He allows that he has been working in the region for a long time and had previously been in Belgian service in Rwanda and elsewhere, by which I am made to understand means Belgian intelligence. The interview takes place on an Indian military base next to a ruined building that was a former palace of the ex-dicator, Mobutu, and has a fine view looking south from Goma over Lake Kivu with the mountains of the Massisi plateau in the distance.

Mr. X, who asks that he not be named, is a large avuncular man with a deep bronchial laugh who rolls his own cigarettes and looks like nothing could surprise him. He allows that he has been working in the region for a long time and had previously been in Belgian service in Rwanda and elsewhere, by which I am made to understand means Belgian intelligence. The interview takes place on an Indian military base next to a ruined building that was a former palace of the ex-dicator, Mobutu, and has a fine view looking south from Goma over Lake Kivu with the mountains of the Massisi plateau in the distance.

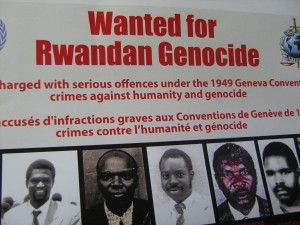

He is the provincial director of the DDRRR programme and his job is to get the rank and file soldiers of the FDLR rebels—among others—to give up voluntarily and accept to be repatriated back to Rwanda. Other groups are the Lord’s Resistance Army and ADF-NAU from Uganda. His programme conducts constant outreach to get this message across that it is safe and desirable to return home. The sensitisation techniques they use are radio, and even face to face discussion where this is possible, and encouraging them to surrender. This is aimed at pretty much all of the FLDR, there are actually few real genocidaires left—there are only 13 who are still sought by the ICC. He pulls a wild west style “Wanted for Genocide” poster out of his desk to show me. Most of the active soldiers and junior officers are too young to have participated in the genocide and they are either the offspring of Rwandans or came here when they were quite young. They have integrated into Congolese society to some extent, but are still essentially a Rwandan Hutu movement that is a predatory group rather than a popular one.

The FDLR has been disrupted quite severely by the current joint army and UN operations and has or is losing access to resources, particularly mining which he believes is essentially over for them. This is fueling greater violence on their part and there have been four attacks on the government army in the last two weeks. Hardliners are trying to re-establish control and this is a group that will never give up. He believes that military pressure needs to keep being applied and that although an endgame is not necessarily in view the defeat of FDLR is closer now than it has ever been, although it will be a longer term process. There is more that could be done to close off their international links, such as phone calls to and action by their civilian support networks from among the Rwandan diaspora in foreign countries, particularly France and Belgium. Neither country supports the FDLR, only that they could be more active in discouraging it if they wished.

He says that his programme is essentially at the end of “a corridor” that the FDLR members need to reach themselves, as otherwise there is a war going on against them and that presenting them with a safe opportunity to defect is half the struggle, as much as convincing them to give up what have become desperate and miserable lives in the jungle.

***

Goma to Rushuro

Meeting up with the UN convoy leaving for Rushuro I reach the base of the Indian Battalion (IndBatt) and am led through the gates to where the convoy is forming up. The soldiers milling around by the trucks all address me as “Sir” but the main things they immediately want to know are how much my camera costs, whether I play cricket, and if I agree that the Congolese army is shit. This is a supply convoy of five large army trucks and goes to the base in Rushuro twice a week. I climb in and take the back seat together with soldiers with rifles and we set off from Goma, leaving the outskirts and crossing the fresh lava fields on the slopes of the volcano. When the lava cools its splits into chunks and the lava fields are a plain of rocks and rubble interspersed with huts and fields. The countryside and the Volcano is otherwise lush tropical green and the mix of this and the lava fields is alternately a Heronius Bosch landscape or a setting for King Kong or Jurassic Park. We are also nearing the border of the troubled and beautiful Virunga National Park that has carried on through decades of war and chaos and manages to survive, just, despite being a base of the FDLR rebels and other armed groups and losing both some of its mountain gorillas and—a remarkable—120 park rangers.

When the UN vehicles reach military road blocks we are waived through. This is a huge relief—road blocks manned by soldiers in Africa are a thing to dread. Less than actual threat there is the inevitable and tiresome process of inquiry, both pedantic and menacing. At its best it is frustrating and at its worst, something far worse. I am beginning to feel enormously grateful to be in the care of the Indian Army. When we pull abreast of the roadblocks the soldiers stare up languidly and watch the truck go by. When they see my white face the expressions change immediately—there is surprise, followed by disappointment and snarls. Some even run after the truck shouting. The big walking dollar sign that Europeans are frequently seen as in Africa is slipping away. After a while I am beginning to enjoy this—I stare back defiantly and even snap pictures.

Heading north we begin coming across Congolese army foot patrols on the road and the military trucks we pass are carrying passengers and freight as much as soldiers; the army is paid infrequently here and money making activity, “debroulez-vous” or take care of yourself, is what soldiers do to get by. I search the faces of the soldiers for some sign of what their lot in life is. Some allow an occasional smile but most look very hard, even weary of a life that cannot be easy. Although these men have power and abuse it I cannot help but feel for the wretchedness of their lot, living, fighting—and dying—under awful conditions without equipment or pay, hated by the communities they pass through and prey upon.

***

At noon we pull off the road and up a track to a small hilltop UN military base. It is surrounded by rolls of barbed wire and has two armoured personnel carriers, a few trucks and jeeps and rows of barrack tents. There are 52 Indian soldiers staying here in what is a forward base or, in army jargon, a Temporary Operating Base (TOB). I am greeted by 26 year old lieutenant Sanjay Kumar Veenia, who is acting commander. Lunch is served by a soldier who pours a pitcher of water for me to wash my hands and offers a clean towel hanging from his arm. The food is more than reasonable—there is dhal, alloo-gobi, okra, butter chicken, chipattis and rice—roughly what you would expect at an inexpensive Indian restaurant in a North American city, and we eat sitting outside under a grass roof gazebo with a spectacular view of the valley and the Virunga mountains.

At noon we pull off the road and up a track to a small hilltop UN military base. It is surrounded by rolls of barbed wire and has two armoured personnel carriers, a few trucks and jeeps and rows of barrack tents. There are 52 Indian soldiers staying here in what is a forward base or, in army jargon, a Temporary Operating Base (TOB). I am greeted by 26 year old lieutenant Sanjay Kumar Veenia, who is acting commander. Lunch is served by a soldier who pours a pitcher of water for me to wash my hands and offers a clean towel hanging from his arm. The food is more than reasonable—there is dhal, alloo-gobi, okra, butter chicken, chipattis and rice—roughly what you would expect at an inexpensive Indian restaurant in a North American city, and we eat sitting outside under a grass roof gazebo with a spectacular view of the valley and the Virunga mountains.

The lieutenant explains that where we are is a forward base for mounting patrols and his job is to: “dominate this axis” against what he calls “anti-social elements”. Day and night patrols are operated in the area with a section—10 soldiers—out on patrol at all times with a rapid response back-up unit on stand by. He says that the FDLR is not frequently active here, but gestures toward the mountainous Tonga Ridge in the near distance and says “they are over there, in the jungle”. It is still a hot zone and attacks occur although mostly the problems are looting by what he calls “bandits”. He won’t be drawn on who the bandits are but it is obvious that the infrequently paid government army and police have a role in this although there are several other armed groups active including the Mai-Mai militias as well as the FDLR. Vehicles of the UN and NGOs are a target and the stopping and looting of agency vehicles is common. There will even be an attack on a UN vehicle on this road today in which a driver is killed. As we leave the base to rejoin the main road a check point closes behind us. We have to reach Rushuru town before night fall.

***

Rushuro town

It takes the rest of the day to cross the potholed roads of Rushuro district skirting the Virunga mountains and we reach Rushuro town, the district capital, and arrive at the MONUC military base at dusk. This is the regional headquarters of the 5th battalion of the Garhwal Rifles—formed by the British Army in 1887 in Garhwal, India, now Uttarakhand Province. A sub-Himalayan area—many of the soldiers have mildly Asiatic features—the battalion’s own official history notes, with some political incorrectness, that the people of Garhwal are “simple, honest and faithful, which forms the bedrock of soldierly character”. Most of the officer corps are from elsewhere in India. The Anglo Imperial influence on Indian military traditions is apparent and, besides bagpipes, drums and bugles, the base is peppered with large print quotations from Lord Alfred Tennyson’s Charge of the Light Brigade: “Theirs not to make reply; their’s not to reason why; there’s but to do or die”. Also highly visible is the rather hopeful banner statement: “The United Nations has no enemies”.

My press liaison officer is the voluble young Captain Alamu from Tamil Nadu state in southern Indian who studied electrical engineering and has been in the army for four years, probably, I suspect, to pay off school and other debts. We establish a programme for the next day which includes, a full military briefing from a company commander, visit to the Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp, participation in their day and night patrols and anything else I wish to do. She says their main objectives are to stabilise the area and respond to “anti-social behaviour”—anything from looting and rape to killings. This is still common in this semi-stabilised area and the cultprits are described as the FDLR or bandits. The identity of the “bandits” is a major issue as they never seem to be definitively identified, beyond being men in uniform with arms which includes the FDLR, Mai-Mai, freelance bandits or the government army and police. The attacks happen right in town, and in fact there will end up being two serious ones this night. The captain says there is a night patrol leaving in half an hour I can join and which will stay out till 5AM. “They are going to Katembe Farm, there is live fire from there from time to time”. I decline for the moment—the day started at 4AM for me and I have still to find a hotel and check-in as I cannot stay on base.

One of the night patrols is to drop me off at a hotel and while I wait at the gate the soldiers are forming up before cocking their rifles in unison in preparation for going out, followed by a short chant which is an ode to the Hindu God Vishnu; the patrols are done jointly with the Congolese army whose soldiers enter the base and are a ragged lot next to the smart drilling of the Indians. A Major takes me in his jeep and drops me off at a hotel which is a brick walled compound with rooms surrounding a courtyard with a grass hut and a cooking fire in the corner. I ask whether he would let his daughter stay here and he laughs but advises me not to leave the hotel at night before driving off. The hotel is full and I hail a motorcycle taxi and look for another, which is at the end of town just before the military check point on the road that leads north to the Virunga Park and Lake Edward. There is no water, except for a bucket, but the room has a clean cement floor and a mosquito net and costs US$15/night. There is a bar in the courtyard—most of the guests are army and police officers—and the music plays loud and late. The music, Congo’s frenetic guitar-based pop overlaid with lyrics in Lingala, the national lingua franca born of river traffic, is haunting and beautiful, both exuberant and sorrowful, like the country.

One of the night patrols is to drop me off at a hotel and while I wait at the gate the soldiers are forming up before cocking their rifles in unison in preparation for going out, followed by a short chant which is an ode to the Hindu God Vishnu; the patrols are done jointly with the Congolese army whose soldiers enter the base and are a ragged lot next to the smart drilling of the Indians. A Major takes me in his jeep and drops me off at a hotel which is a brick walled compound with rooms surrounding a courtyard with a grass hut and a cooking fire in the corner. I ask whether he would let his daughter stay here and he laughs but advises me not to leave the hotel at night before driving off. The hotel is full and I hail a motorcycle taxi and look for another, which is at the end of town just before the military check point on the road that leads north to the Virunga Park and Lake Edward. There is no water, except for a bucket, but the room has a clean cement floor and a mosquito net and costs US$15/night. There is a bar in the courtyard—most of the guests are army and police officers—and the music plays loud and late. The music, Congo’s frenetic guitar-based pop overlaid with lyrics in Lingala, the national lingua franca born of river traffic, is haunting and beautiful, both exuberant and sorrowful, like the country.

I go for a short walk on the road—I hate the idea of being trapped in the hotel and not knowing my surroundings or the people I am with. There are some shops and small market stalls and I buy some bottled water and look for something to eat but all I can find are “high energy glucose-protein biscuits” that look like they came from an emergency feeding centre. I exchange pleasantries on the road and there are some muttered replies but there are no easy smiles in this town, this town which has suffered much and changed hands many times. Most recently that was in October when it fell to forces of the CNDP and the government army sent packing.

A change of power by force of arms is a traumatic event in this, or any, area—there is looting, disorder and the settling of scores as well as a change of elites. In Rushuro that included atrocities against those collaborating with the outgoing government regime, including the Mai-Mai self-defence militias. There is no precise number attached to the killings involved but by many accounts they were substantial. The UN human rights office in Goma told me they are still pursuing some of these cases and there may even be some prosecutions of CNDP officers because of it, although this flies in the face of expediency. Even now the head of the CNDP, Jean-Bosco Nstanga is wanted at the International Criminal Court in the Hague for war crimes but it would plainly be a disaster to try and act on that now. A subsequent peace agreement between the two sides has resulted in the CNDP merging back into the government army again but the process is weak, and the identity concept of a single national army is more notional than real; much of the CNDP carries on as before. There is also the risk that they will opt out of the process again at any time and plunge the province back into a new round of conflict on top of all the ones already in course. In Rushuro there are added tensions from the fact that the CNDP soldiers are now paid less frequently than when their own side was in control, and the town is afflicted with all the problems that flow form being occupied by an army of unpaid soldiers. Although MONUC and the Indians officially try not to recognise any differences between the government and CNDP soldiers, it is obvious that having fought each other for the past year, relations are neither good nor close and that this is a serious problem area.

Walking across the road back to the hotel a man gestures me toward his shop, which is little more than a market stall made of rough boards and inside he pulls out a ragged piece of paper which he shows to me. Across the top is written “The Day of the Catastrophe” and below is an inventory of items each with a value—2 boxes soap, 2 boxes matches, razor blades etc, and at the bottom a total— $340.11. This is a princely sum in this area. He explains this is what he lost when his stall was looted by the CNDP after it took over the town in October. The soldiers came down the street and kicked down the doors of all the shops and took whatever they needed. The “day of the catastrophe” —October 10th—is an important date for this man, it is the day he was ruined financially.

***

Hailing a motorcycle taxi in the morning to get to the UN base on the way there is a crowd on the road. When they see a white face there is a ripple of agitation and then the crowd surges forward. The motorcycle driver immediately diverts off the road and down a muddy track between mud huts pursued by the crowd which slowly thins out. We follow muddy trails through this shanty town and divert back to the road past the road block and arrive at the UN base. I ask the driver what was going on but he cannot speak French enough to explain to me and does not appear too concerned.

Hailing a motorcycle taxi in the morning to get to the UN base on the way there is a crowd on the road. When they see a white face there is a ripple of agitation and then the crowd surges forward. The motorcycle driver immediately diverts off the road and down a muddy track between mud huts pursued by the crowd which slowly thins out. We follow muddy trails through this shanty town and divert back to the road past the road block and arrive at the UN base. I ask the driver what was going on but he cannot speak French enough to explain to me and does not appear too concerned.

Captain Alamu is heading for a meeting with the district administrator and on the way we encounter the same vaguely menacing group blocking the road. Captain Alamu halts our vehicle, gets out and wades into the crowd followed by a group of Indian soldiers with rifles who jump down off the back of the pick up truck.

The road block is being manned by youths from the motorcycle-taxi association who are stopping traffic and demanding contributions for the funeral of one of their drivers—which is to take place here later in the day—although it has become a crowd and there is a whiff of alcohol even now in mid-morning. There has been a FDLR or bandit attack on the outskirts of town last night in which homes were looted and the moto-taxi driver killed. Four women were abducted and were being dragged away until a MONUC patrol intervened and the gunmen abandoned their hostages and fled into the bush. The youths claim that the donations are “voluntary” although through an interpreter Captain Alamu says they must not obstruct traffic or extort money. Back in the truck she turns to me and explains that this kind of intervention or mediation is what she does all day.

Arriving at the main government office in Rushuro we are led into the district administrator’s office. Sitting behind a desk wearing dark framed glasses and a blue button down shirt is the district chief—the most senior civilian in Rushuro. He is dignified, even bookish, and I find later that he is descended from tribal royalty. I imagine him in another life as the dean of a small college in Europe or the American mid-west. The Captain is here to get approval for building a new school as one of the MONUC social projects and we settle our business quickly. He then turns to me and asks what I want to know or do in his district. I explain my business and then ask him what his greatest problems and priorities are. He seems startled by the obviousness of the question and explodes:

“We need peace!” He stops for a moment and repeats more calmly: “we need peace, then we need development. But first we need peace. There was gunfire directly in front of my house last night, 300 yards from here. Someone was shot and $450 stolen from a vehicle. My wife and I were hiding under the bed and calling MONUC. They took 20 minutes to arrive”.

“15 minutes” Captain Alamu corrects him.

“When there is a house on fire do you open the window to admire the view or do you put it out? And did you catch them?”

“We have launched an investigation. The gunmen ran into the bush afterward and we could not follow them”.

“But you never finish the investigation and find out who it is”. He lets out a quiet sigh of resignation as though this awfulness is the sad fate of the town he loves and changes the topic.

All through this conversation I am fascinated by a picture on the wall above his desk. It is a black and white photograph in a wood frame from the early 1960s and is of a cocktail party scene. There is a middle aged European man wearing a light suit and his wife in a floral cocktail dress flanking an African man in an officers uniform. They are all smiling and holding drinks in what is a drawing room with nice furniture and paintings on the wall. It is obviously from the late colonial period, probably right here in this town, and I immediately see the racial overtones. Asking permission to take a picture of it I offer the embarrassed disclaimer that it is from the “mauvaise temps coloniale”. He stares back at me and says simply: “that is the most beautiful thing in my office”. I look at the photograph again; the ordinariness, even banality, of the cocktail scene, the smiling couple and the officer, and realise that for this cultured and courteous man the picture is the embodiment of the peace and civility he craves for his area, now a war zone of violence and suffering.

All through this conversation I am fascinated by a picture on the wall above his desk. It is a black and white photograph in a wood frame from the early 1960s and is of a cocktail party scene. There is a middle aged European man wearing a light suit and his wife in a floral cocktail dress flanking an African man in an officers uniform. They are all smiling and holding drinks in what is a drawing room with nice furniture and paintings on the wall. It is obviously from the late colonial period, probably right here in this town, and I immediately see the racial overtones. Asking permission to take a picture of it I offer the embarrassed disclaimer that it is from the “mauvaise temps coloniale”. He stares back at me and says simply: “that is the most beautiful thing in my office”. I look at the photograph again; the ordinariness, even banality, of the cocktail scene, the smiling couple and the officer, and realise that for this cultured and courteous man the picture is the embodiment of the peace and civility he craves for his area, now a war zone of violence and suffering.

Outside the office is flanked by two UN tanks and the soldiers atop of them salute Captain Alamu as we emerge from the building. The tanks have been there since this morning, a response to the attacks of last night. It seems like shutting the gate after the horse is gone. The attack that the district administrator spoke of is significant. That it was brazen enough to take place in the centre of town—against a truck contracted to carry supplies for the UN World Food Programme—is a challenge to the authority of MONUC and their ability to maintain peace in Rushuro. That a large amount of money was stolen also seems to indicate that it was by people who had information and acted on it. Who the gunmen and the bandits are is the great mystery of this town. It is a secret no one wishes to address. If the question was asked where was MONCU when this happens, it also has to be asked, where were the police and the Congolese army? Or were they perhaps there all the time. However much the UN is held accountable for the disorder of Rushuro, they are quite explicit that their role is to back up the Congolese authorities not substitute for them, although that line is crossed again and again as they are called on to step in and assume the roles a weak state cannot provide.

Returning back through town the young men are still on the road collecting for the funeral of the moto-taxi driver; as we come abreast I can see their eyes are bloodshot and they are visibly drunk on banana beer; some of them beat on the side of the vehicle as we pass through the crowd.

***

The Situation Room, MONUC Base, Rushuro

My briefing on the local security situation is to be delivered by Major Dalgish, commander of one of the base’s four companies, and a perfect speaker of English—a rarer than expected commodity here in the Indian Army. I am led into the Situation Room, a large tent set up like a class room with seats in front of a screen, flanked by maps of the area. In the far back corner is a long table at which an officer is speaking into a radio and directing the various patrols together with a soldier and translator responding to a bank of cell phones that are part of the unit’s surveillance and rapid response system.

As this 911 team operates in the back ground Major Dalgish strides to the front of the room, offers me one of the easy chairs, and begins advancing through a Power Point presentation. The area he is responsible for in his sector, Rushuro district, is newly stabilised but he admits that the process is neither complete nor perfect. There are still multiple armed groups operating here and the process of integrating the army, CNDP and the Mai-Mai militias is an uneven success. The CNDP had pulled out of the FARDC—they had never really been fully integrated anyway—and last August launched their rebellion in which the government forces were quickly defeated and kicked out of the district, retreating all the way to Goma. The CNDP took over Rushuro town at that time—all NGOs and other UN civilian staff having previously been evacuated—although the MONUC forces remained in town, but largely confined to their base. This was an extremely difficult period. The local population, according to the Indians, “went wild”, there was widespread looting, UN vehicles were stoned and the CNDP exacted retribution against those that had opposed them. He doesn’t say it, but this was a dark period for MONUC too as it was exposed as being essentially powerless to prevent the collapse of government forces, the triumph of the CNDP or the killings and serious human rights abuses that followed. This inflicted political damage that MONUC has been attempting to recover from ever since, as well as to the entire peace process both in the Kivus and the DRC which had unraveled over the past year, undoing five years of peace building.

The CNDP have since re-joined the FARDC and being three brigades strong, still dominate the military presence in the area. They are also local, with most of their officers drawn from the Tutsi community who account for 8% of the district’s population. Most of the rest of the rest—70%—are Hutus, nominally the ethnic kinsmen of the genocidal Rwandan FDLR.

The FDLR are still active in the district and number battalion strength with 600-800 soldiers and are divided into two groups, FDLR Soki—led by Major Soki—and FDLR RUD, which is led by a Colonel Tata. They are still most active in Nyakoma and Nyamilima, north of Rushuro, the former just 25km away. Since the joint military operations of the FARDC and the Rwandan army in January-February—the FDLR has been chased out of the population centres they formerly held and have been expelled to the bush. He shows aerial photographs of areas previously held by the FDLR, including a lakeside town that shows an FDLR camp that was living off of it, a short distance away in a defined camp area; “They are led by ex-army officers and are very organised”.

The FARDC and MONUC are continuing joint military operations against the FDLR—Operation Kima II—with MONUC providing logistical support—aerial reconnaissance, supplies, transportation, and joint strategic planning advice, but are forbidden from engaging in active combat operations unless fired upon. There are active combat operations against FDLR emplacements going on right now to the north of town—31 FDLR combatants have been killed in the past month and 48 have surrendered. Elsewhere MONUC is operating patrols to provide local security and deter armed incursions.

He says that the objectives for the area are to:

- Create a secure environment;

- Protect civilians;

- Empower civil administration;

- Enable UN and NGO humanitarian operations and;

- Revive hope.

This last objective—revive hope—is crucial and is an open admission that the local population has suffered enormously and had lost faith in the peace process as well as in their government and the UN during the upheavals of the past year, one more false dawn among many over 15 years of warfare.

He says that their main objectives are to stabilise the area and that MONUC is doing this both through extensive patrols to provide confidence and safety as well as running a surveillance and intelligence gathering system. The latter involves identifying key informants and providing them with cell phone with which to call if there are any problems. This includes local village chiefs and community leaders, NGOs, the police and army, and bar owners in town. The bars are where trouble frequently happens and owners are under orders to call if anyone enters with a gun. Another group that has been recruited is a women’s association which acts on behalf of rape victims. This is a plague all over the Kivus and there are signs throughout town warning against sexual violence—illustrated with a disturbing graphic of a man with a gun attacking a woman—and with an emergency response number posted. The UN base calls each of these contacts ever day, particularly at night. The UN emergency numbers are also sign posted and broadcast by radio and he explains that there is a continuous process of information gathering with rapid response teams dispatched whenever trouble arises. It is an elaborate system, and considering its incongruous, out of place, service oriented culture, the “MONUC, how can we help you” signs, the “Who you gonna’ call?” ethos I am reminded that there is nothing trivial about this—for people living under conditions of abuse and impunity this is almost the only life-line available.